When most people think of mining towns, they might not think of the Adirondacks.

Yet, this form of settlement shaped many towns here. One of them still lies deep within one of the most remote areas of these mountains, and it has a mining history that stretches further than all the others.

Early development

The original mining town was built as part of the first wave of European settlements. Archibald McIntyre and David Henderson were guided to the site by a member of the Abenaki tribe, Lewis Elijah Benedict. The ore deposits were so impressive the two men created the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company.

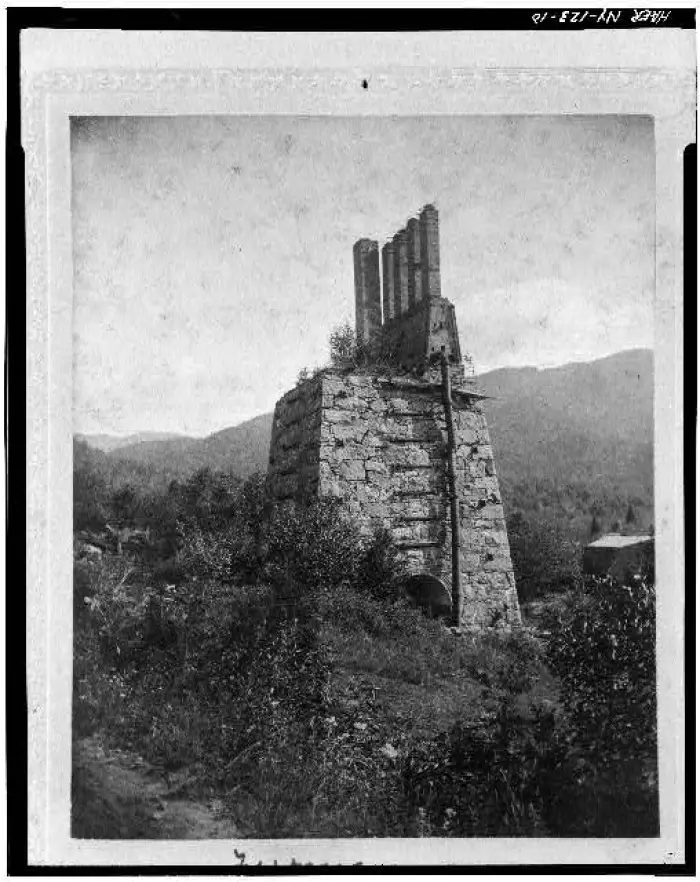

The difficulty of reaching the site makes the majesty of the enormous blast furnaces they managed to construct even more impressive. Known as the Upper Works, the almost 60-foot-tall furnace was powered by a diversion of the Hudson River, which tumbles southward from the nearby High Peaks, a rugged group of mountains that tower over 4,000 feet in elevation. The iron was of such high quality it sold for twice the usual price.

The incentive of the high quality iron carried them through some daunting challenges, such as the difficulty of getting supplies in, and product out, on the crude roads built out to the site. Besides the logistical difficulties, there was a continuing struggle with the ore having some mysterious element which was difficult to manage with the technology of the period.

The young mining company recruited workers and built a village with help from the McIntyre Bank, the first bank in the Adirondacks. Even the village was named McIntyre, but it was later re-named Adirondac. Archibald McIntyre, as a prominent politician as well as an entrepreneur, also gave his (misspelled) name to the MacIntyre Range, which includes the mountains Iroquois, Boundary, Marshall, Wright, and Algonquin, the latter of which is the second highest peak in the state.

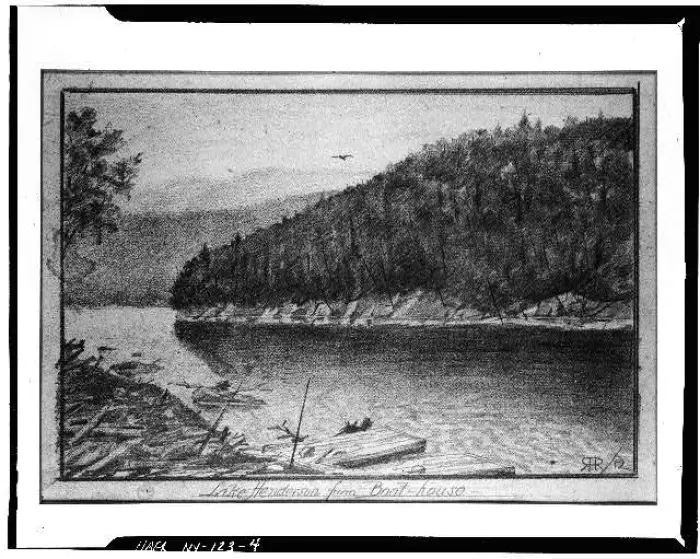

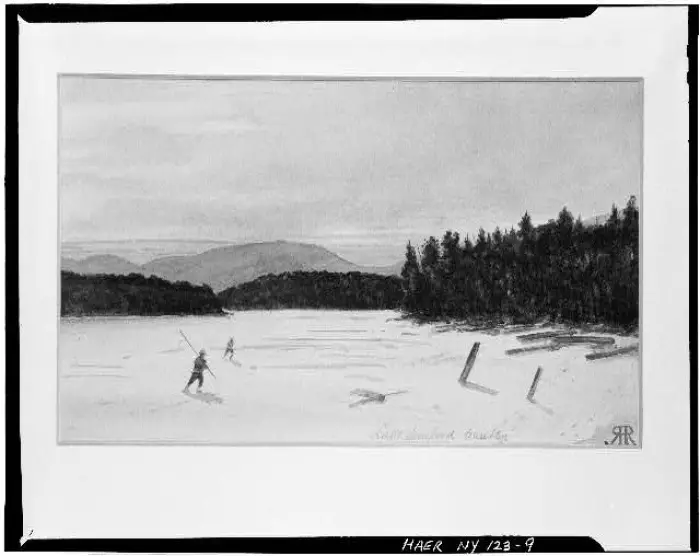

David Henderson gave his name to Lake Henderson, and then, sadly, to Calamity Pond. An accidental discharge from his pistol led to his death there in 1845.

Henderson's energy, leadership, and technical expertise had been vital to the operation. The Sackett’s Harbor and Saratoga Railroad Company were going to build their railway to Adirondac, but the geographic obstacles were too great. By 1856, the mining operation and its supporting village were abandoned.

Sportsman's paradise

As the forest slowly reclaimed the 10,000 acres of the Tahawus Tract, it became popular for use by private hunting and fishing clubs. In 1876, the Preston Ponds Club leased the land from the Adirondack Iron Works Company and renamed themselves the Tahawus Club. This gave the village its third name, Tahawus. Tahawus, which means cloud-splitter, was also the original name of Mount Marcy, the highest mountain in the Adirondacks.

Then-Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was visiting the Tahawus Club in 1901, pausing on his way to Buffalo, when he received a message that President William McKinley was expected to recover from a recent assassination attempt. Roosevelt was hiking Mount Marcy when he got the news that the president's health had taken a turn for the worse. Thus began Roosevelt's famous Midnight Ride to the Presidency. During his hurried trip to Buffalo, Roosevelt learned McKinley had died from his injuries, making him the new president. Every fall, Roosevelt's historic visit is the focus of the town of Newcomb's Teddy Roosevelt Weekend.

Rebirth of the mine

It turned out, the titanium dioxide that was one of the reasons for the first mine's closure led to the rebirth of Tahawus in 1941. In the decades since the mine was abandoned, titanium became recognized as a metallurgic "wonder metal." It could be mixed with other elements to produce strong, lightweight, corrosion-resistant alloys which transformed the fields of aerospace and military technology, industrial and automotive processes, medical and dental instruments, and the sports and computer industries.

The wartime demand for titanium led to the federal government completing the railroad line into the mine site to secure a domestic supply. National Lead Industries successfully extracted 40 million tons of titanium by the time the mine closed again in 1989.

The Tahawus mine would become the largest titanium mine in the world. Tawahus the town was to remain inhabited until 1962, when the employees and many of the buildings were relocated to the nearby town of Newcomb.

The Newcomb Historical Museum recently completed an exhibit about the mining town's history.

Now, the old mining town is a popular hiking destination within a managed forest. The McIntyre Blast Furnace had its site cleared and its furnace stack stabilized and cleaned by the Open Space Institute, which purchased the area in August 2003 and manages it with a Department of Environmental Conservation partnership. County Route 25, Tahawus Road, brings drivers northward to Henderson Lake, and connects with State Route 28N to the south. It makes a beautiful scenic drive.

Adirondack history is not confined to just the Adirondacks. It is surprising how often it has influenced the history of New York, and the whole nation, as the largest publicly protected area in the contiguous United States. But unlike many such places, the towns that sprang up in the beginning are still places for people to live and work. The Adirondacks continue to offer lessons in how to conserve natural beauty, and help it work in partnership with human civilization.

Find a charming place to stay. Enjoy local dining. Visit local museums for more fascinating glimpses into the Adirondacks.

Header photo by AH7 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons